A black cloud floated across my sun last month, with a sinister announcement from the Prefecture de Police. They let me know, with big logo and one line of faded type, that I had just one point left on my driver’s license.

My blood ran cold. The thing I’d dreaded was coming to pass.

You see, the French driver’s license is a hard-won document. Once you’ve got it, you NEVER want to lose it because getting it back is torturous. But the system is such that you are almost bound to lose it. Here is how it works.

The license comes with twelve points. Those points are balanced on the head of a pin, and can drop off at any time. There are infractions involved, and there is no mercy. If you lose those points, you lose the license, and there are near insurmountable obstacles to getting it back.

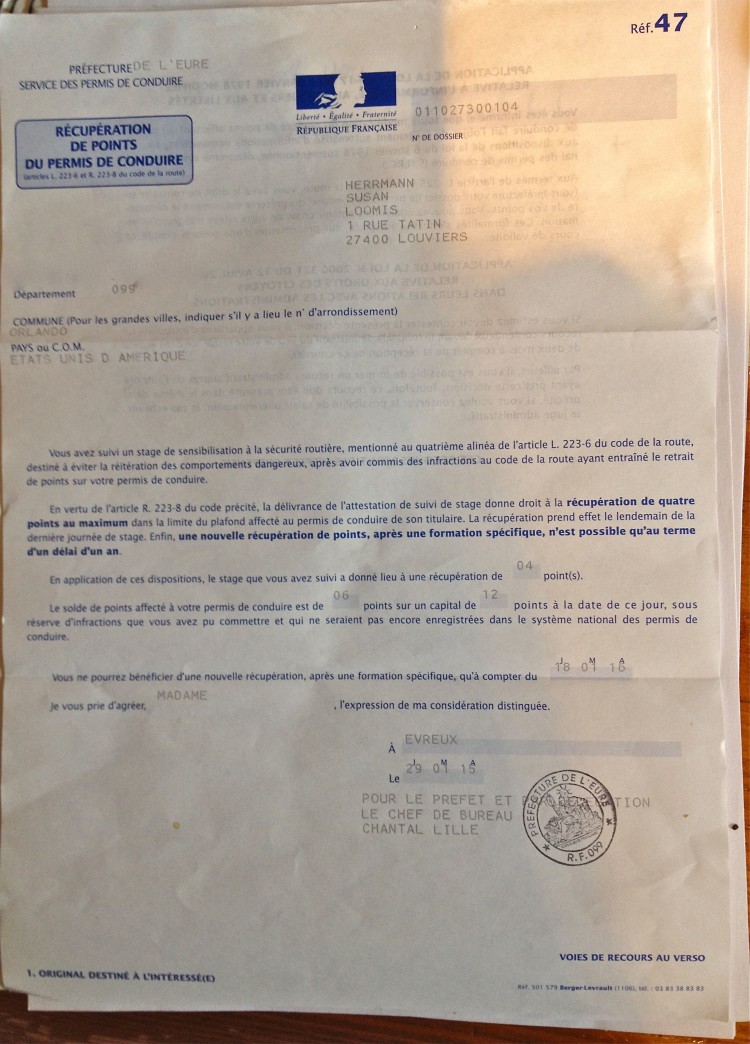

I had one option, and one option only – the dreaded stage de récuperation de points where, for fourteen hours one submits to the harsh realities of one’s transgressions. I signed up immediately, learning to my dismay that this sacrifice of my precious time would net me a measly four points, giving me a total of five. As I immediately discovered at the stage, having five points is almost like having none, because the points are so easy to lose.

I should know. I lost six over the recent holidays, driving my son back and forth to CHURCH. I was performing pious duty but the machines that flash when you exceed the speed limit on country roads where you don’t even realize there is a speed limit, don’t care. And, the speed limits on these funny little roads, and the autoroute, and every road in between, change all the time, particularly of late as the bankrupt government searches for revenue. What was once a safe little 70 zone becomes a 50 zone overnight. The nasty little sign indicating this seems all too often to be hidden in the trees.

We were twenty-four offenders at the stage, the youngest 19, the eldest 82. We came from ALL walks of life, and we included some party boys who all but tried to sell their favorite drugs to us during the lunch break. There were two animateurs, a psychologist with slopey shoulders, a wobbly paunch and a lisp that made his southern French almost impossible to comprehend when he said the few words he had to say, and a puffy-faced woman who looked and acted like a drill sergeant right out of central casting, only she was French.

“Booonnnnn,” she said, her hard eyes locking with each of ours. “What are you here for?” and she went around the table, as we each confessed our sins. “You’re lucky you’re in France,” she said, spinning on her heel. “There isn’t another country that allows its drivers to recuperate their points.”

She proceeded to scare us all to death, recounting stories of drunks getting caught and thrown en taule, in the slammer, speeders being maimed for life, telephone talkers killing pedestrians. “We think we have a terrorist problem in this country?” she said. “More people are killed by people like you than in any terrorist acts.”

The more she talked, alternating between a frantic whisper and a Shakespearean soliloquoy, the more we collectively slunk down in our seats. We’d all been bad, and we were there to pay.

We also learned about every aspect of her life (married to a farmer, parents still living, mother of a fifteen year old who isn’t allowed a cell phone). And we learned all about her taste for extreme sports and her pôtes, or friends, of which she had – I counted them – at least 800. They were all transgressors like us, most desperately poor and bereft because they’d lost all their points.

She was into tough love; she was intimidating; she was theatrical; she bought each of us coffee after lunch; she taught us to fear the “man”; to put down our phones in the car; to leave ten minutes early so we wouldn’t speed. She tried to get us each to buy an electronic Breathalyzer for the car (100€); she called some of us losers, and the rest of us idiots; she warned us that if we didn’t change we’d end up walking; she said, over and over, that she had no power to intercede for us in any way.

Being French, I’d hoped to learn some tricks to keep my small cache of points (we get by in this country with tricks). I wasn’t sure what kind of tricks – smoking a cigarette before taking the wheel after a drink or two (it’s supposed to negate the alcohol); getting a GPS that beeps at speed traps (they’re illegal – everyone uses one which is an example of a trick); flirting with a police officer who stops the car.

I’m kidding of course.

By stage’s end, she’d done her job well. We were all petrified. We all felt lucky not to be in jail. We all vowed that we would turn over new leaves. I’m serious. There was a bonding around that table, the glue being our rolled eyes as she turned her back after her tenth story of her and her pôtes eating and drinking all night, our fear when she stomped her foot for emphasis, our dismay that she wouldn’t intercede for us, even if she could.

At the end of it, we unstuck ourselves from our chairs and shook hands all around. “We’re part of a family now,” one of the gentlemen said as he nodded and climbed into his BMW. In a normal situation we would all, I am certain, have headed to the local bar to celebrate our deliverance. But we didn’t, knowing that after the two tiny glasses of wine allowed under the law, there would have been no one to drive us home.

I must say the tough love worked for me. I’ve been a model driver since my stage, heeding the speed limit though my zippy little Citroen begs to go faster; taking slower turns, rethinking the role of my car which I’d considered an ideal place to knock off phone calls. No more. One can only take the stage de récuperation three times in a lifetime, and it can only be repeated after twelve months and one day.

So, I’ve got to behave and keep those precious points. In three years, I automatically get the full complement back, if I haven’t transgressed. I wonder what the chance of that really is.